A reader asks:

My asset allocation has been pretty conservative since the market run-up in 2020. My basic thesis is that the market is overvalued, and the only way I can keep myself in equities at all is to have a 60/40 stock/bond allocation. One thing I like about having the 60/40 split is that it gives me the option of changing to a more aggressive allocation if stock valuations fall. I have nagging doubts that my allocation is not aggressive enough given my age (41), so I’ve been thinking about how I could convince myself to be more aggressive. Over the last week, I’ve been trying to commit a simple strategy to paper. Ideally, my strategy would have a line like “If X metric of market valuation goes below Y, change to more aggressive asset allocation.” This has made me realize that I don’t know a good way to do this. I’ve used the cyclically adjusted p/e of the S&P 500 to convince myself that stocks are overvalued, but I don’t know if it can be used as an indicator for my plan. Price to peak earnings seems like another option. I’m curious if you can offer a better method or indicator, or if you hate the idea of this ‘market timing light’ in general.

I do love the idea of investing based on a pre-established plan.

Making good decisions ahead of time is one of the best ways to override the lesser version of yourself, especially when emotions are running high during a bear market.

It also makes sense to use your fixed income allocation as dry powder. If you want to buy when there’s blood in the streets, you need a source of liquidity. That’s one of the beauties of a diversified portfolio.

Overrebalancing when stocks are down sounds like another wise move. This is the kind of thing where you can place bands or ranges around your allocations that help determine how aggressive you can get when stocks are on sale.

Where you lost me is using valuations to time the stock market.

I’ve never found a legitimate way to utilize valuations to determine entry or exit points in the stock market. Maybe when things get to extremes but even then valuations can be unreliable.

In early 2017, I wrote a piece for Bloomberg about stock market valuations:

This was the lede:

Something happened in the stock market this week that has only occurred twice since 1871: Robert Shiller’s favorite valuation method for the S&P 500, the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, reached 30. So, is it time to worry?

The only other times in history when the CAPE ratio reached 30 were in 1929 and 2000, right before massive market crashes. So it made sense that some investors were worried about the stock market being overvalued.

The S&P 500 is up nearly 170% since then, good enough for annual gains of roughly 14% per year.

Sometimes valuations matter, but other times, the market doesn’t care about your price-to-earnings ratios.

The same is true during bear markets. Sometimes stocks get downright cheap but not all the time.

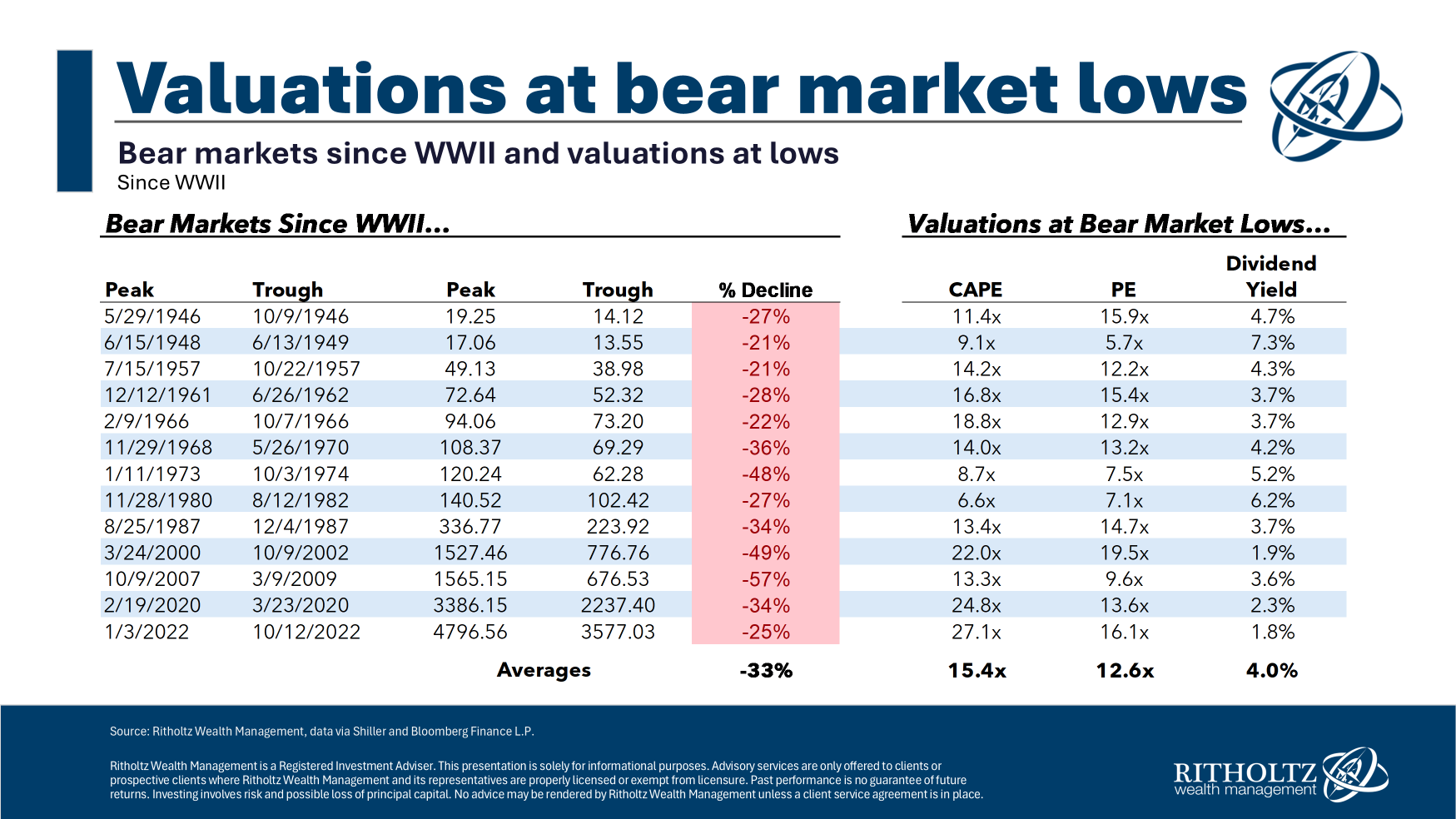

I looked at the CAPE ratio, trailing 12 month P/E ratio and dividend yield on the S&P 500 at the bottom of every bear market since WWII:

The averages might look like solid entry points but averages can be deceiving when it comes to the stock market.

In the past valuations would get to much juicier levels at the bottom of a bear market. But it’s also true that starting valuations in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and 1970s were much lower. Dividend yields were also much higher back than (mainly because there weren’t as many stock buybacks).

Three of the four bear markets this century didn’t see the CAPE ratio come close to previous bear market valuation levels. If your plan was to get more aggressive when the market got cheap enough, you would still be waiting.

The problem with using valuations as a timing indicator is that even if they do work on average, missing out on just one bull market can be devastating. You could be waiting a mighty long time to get back into the stock market and miss out on big gains in the meantime.

I’m not a big fan of market timing in general but if you really want to get more aggressive during a bear market, I prefer using pre-determined loss thresholds.

For example, every time stocks are down 10%, 20%, 30%, etc., move a specified amount or allocation from bonds to stocks. It’s a much simpler plan that takes away the vagaries of valuations over time so you don’t miss out on a buying opportunity. Buying stocks when they’re down is a pretty good strategy.

Granted, no one knows how far stocks will fall in a bear market but I would trust price declines over valuations.

There have been 13 bear markets since the end of WWII, or one every six years or so on average. A double-digit correction happens in two-thirds of every year. You can’t set you watch to these averages but risk is more reliable than valuations in the stock market.

The good news is you didn’t completely get out of stocks because you felt the market is overvalued. Extreme positions are the killer when it comes to market timing.

My typical advice to investors is you should choose an asset allocation you would be comfortable holding during bull markets, bear markets and everything in-between. Getting more conservative or aggressive sounds like an intelligent strategy until you make a mistake at the wrong time.

Market timing is hard. Valuations don’t make it any easier.

We covered this question on the latest episode of Ask the Compound:

My personal tax advisor, Bill Sweet, joined me on the show again this week to tackle questions about optimizing taxable vs. tax-deferred retirement accounts, the 401k trap, rolling over an inherited IRA and the tax considerations from moving aboard.

Further Reading:

The Difference Between Market Timing and Risk Management